From the Repertory | November 14, 2019

|

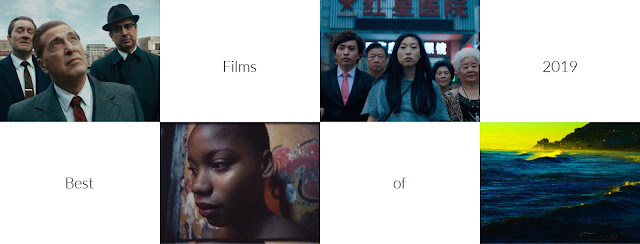

| Kaycee Moore and Nate Hardman in Billy Woodberry's BLESS THEIR LITTLE HEARTS. |

What's new on Blu-Ray and DVD.

THE 3-D NUDIE-CUTIES COLLECTION

In the 1960s, “nudie cuties” were a popular form of scintillating exploitation films before hardcore porn became mainstream in the 70s. This single-disc release from Kino Lorber includes two "classic" nudie-cuties from 1963, The Bellboy and the Playgirls and Adam and the Six Eves. Neither are what you might call "good," are of some historical interest. The Bellboy and the Playgirls was co-directed by none other than Francis Ford Coppola making his feature film debut. Coppola helmed the color 3-D sequences, while Fritz Umgelter handled the bulk of the work. It's a rather bland film (especially considering it was basically supposed to be porn), and there's nothing you wouldn't see in a fairly tame R-rated film today, with topless women making occasional appearances as a hapless bellboy/aspiring house detective discovers that they're lingerie models in the midst of shooting a commercial.Adam and the Six Eves features a lot more nudity, but still nothing particularly shocking by today's standards. The film centers around a chubby treasure hunter who stumbles across a desert oasis populated by beautiful women who are guarding a secret. The film has no dialogue, and is instead narrated by the man's wise-cracking donkey. Some of the one-liners are genuinely funny, but this is one strange film. Its director, John Wallis, never made another film, but in one fell swoop nearly becomes the Ed Wood of porn with the shoddily constructed cardboard sets and truly head-scratching framing device. But in the end, it's just an excuse to ogle naked breasts, and in that regard it delivers on its promise, even if the sight of the treasure hunting hero doing the ogling while his donkey makes fun of him is anything but erotic. Still, they're a fascinating piece of cinema history even if they will mostly be of interest for fans of psychotronic film.

ADAM AND THE SIX EVES - ★ (out of four)

THE BELLBOY AND THE PLAYGIRLS - ★½ (out of four)

BLESS THEIR LITTLE HEARTS (Billy Woodberry, 1983)

Like its spiritual predecessor, Charles Burnett's Killer of Sheep (1978), Billy Woodberry's Bless Their Little Hearts focuses on a black working man in the African American Watts district of Los Angeles. Except in this case, Charlie Banks (Nate Hardman) is more of a *not* working man, because he finds himself perpetually un and under employed, spending his days at home with his harried wife, Andais (Kaycee Moore) and their children.Andais wants him to get a job, while Charlie insists there's no work to be found. This leads to Charlie wandering listlessly through the streets of Watts, and eventually into the bed of a neighbor, leading to a titanic clash between Charlie and Andais that has far-reaching consequences for their family. Moore is so good in this scene, her feelings so real and raw, that Woodberry was reportedly unable to capture a third take. The first take was interrupted when Hardman improvised grabbing Moore, an act that so enraged her that she channeled her emotions into a fiery second take, resulting in a scene that feels almost uncomfortable in its veracity. Woodberry filmed it all in one, single take, with the camera wandering around the Banks' kitchen as if the audience is an unseen third party bearing witness to a domestic dispute that we shouldn't be seeing, but can't possibly escape. In those nearly 10 uninterrupted minutes, Moore channels the energy of a woman who has had enough, fed up with her deadbeat husband's excuses and releasing years worth of pent up frustration.

What makes Bless Their Little Hearts so remarkable is Woodberry's attention to the smallest details, the way in which the fly-on-the-wall nature of the film creates what I like to call a kind of poetry of the mundane. Woodberry sets out to capture a very specific time and place, in this case the African American Watts neighborhood, and the lives of th people in it who are just trying to get by. Poverty is rampant and jobs are scarce, and Woodberry follows his characters as they attempt to find things to fill their empty time. The grainy, black and white cinematography adds another layer of verisimilitude, and every frame is alive with a kind of jittery energy teeming with life, constantly threatening to burst forth from the screen. Woodberry is an unheralded virtuoso, and Bless Their Little Hearts is a revelation that can at long last be given its due.

GRADE - ★★★★ (out of four)

GEBO AND THE SHADOW (Manoel de Oliveira, 2014)

Manoel de Oliveira was 104 years old when he directed Gebo and the Shadow. It would end up being the Portuguese master's final film, but it's the work of a filmmaker who remained prolific and vibrant right up to his last day, churning out such late-period masterworks as Eccentricities of a Blond-Haired Girl (2010) and The Strange Case of Angelica (2010) well into his hundreds. De Oliveira was the last remaining filmmaker from the silent era - his first film, Douro, Faina Fluvial was released in 1931, four years after the advent of sound but before it had fully caught on in Portugal.Over 80 years into his career, the influence of silent film was still keenly felt in de Oliveira's work, mainly in his use of blocking. De Oliveira never moved the camera around much, carefully composing the minimal amount of shots he needed to convey his meaning, often leaving the camera in one place for an entire scene. And yet what could easily be seen as a blocky, static mise-en-scene comes alive, its characters perfectly placed in their surroundings so that their words come to vibrant life. Each frame of a de Olivera film could be hung on a wall as a painting, and Gebo and the Shadow is no different. It's an understated family drama about an old man named Gebo (Michael Lonsdale) whose son, Joao (Ricardo Trêpa) has run away from home and descended into a life of crime. Gebo tries to hide the unsavory details on Joao's life from his wife, Doroteia (Claudia Cardinale), but eventually everything comes to light when Joao shows up back at home unannounced. De Oliveira deftly explores the family dynamics while crafting a moving tale of a man willing to do anything to protect his family.

It tends to get lost a bit in its sometimes rambling dialogue scenes, but de Olivera never loses sight of the plot for long, bringing it all back for a powerful ending that explores the shadow children can cast over a family's entire existence. De Oliveira concocts striking images (the disembodied hands emerging from the darkness in the opening scene feel like something straight out of the silent era) in very confined spaces, leaving us with a film that should feel cramped and claustrophobic but instead feels consistently vibrant and alive, a testament to the extreme talent of its director who ran rings around much younger filmmakers for nearly a century.

GRADE - ★★★ (out of four)

THE LION KING (Jon Favreau, 2019)

The original animated film holds a special place in the hearts of many of us who grew up in the 1990s, and it remains one of Disney's finest achievements of the era. The remake brings very little new to the table - adding a few lines of dialogue here, a reworked song there, but for the most part this new Lion King is content to be a shot-for-shot remake of its predecessor, hitting all the familiar notes fans of the original have come to expect but offering nothing new of any real note. The more realistic animation is certainly eye-popping, but the characters lose something in their transition to more life-like incarnations. They're less expressive and engaging as "real" animals; as such, the film lacks the emotional core that made the original so endearing.In fact, the entire film lacks a certain elegance in its translation to photo-real animation. For all the epic vistas the film shows us, it's impossible not to recall its animated counterpart, and the way in which the colorful drawings of the original Lion King expressed the emotions and feelings of the narrative with such grace. This new Lion King is often thuddingly literal - simply tracking characters trotting through musical numbers rather than bursting into swirls of color and song. For a film full of such breathtakingly real images, the musical numbers are often flatly staged, the realism constantly undercutting the story's vibrant emotions and narrative drive.

GRADE - ★★ (out of four)

TOY STORY 4 (Josh Cooley, 2019)

The idea of a homemade toy finding a home among Bonnie's "real" toys is an appealing one, but it's a conflict that is resolved all-too-quickly in favor of the film's action/adventure plot. The film's villain, a creepy antique doll named Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks) who covets Woody's voice box, is perhaps one of Pixar's most intriguing antagonists. Rather that follow their usual formula of revealing a seemingly benign character to be evil, TOY STORY 4 takes the opposite approach with Gabby Gabby, giving her a poignant twist that subverts what Pixar has conditioned audiences to expect.Nevertheless, there's a strange sense of "been there, done that" to the whole thing. Toy Story 4 is moderately engaging, and it's always nice to spend time with these characters, but it mostly feels like an afterthought to the original trilogy, attempting to take the story in new directions that it didn't really need to go. The existential drama of toys trying to find their purpose and their place has given the series some truly gut-wrenching emotional moments, but nothing in Toy Story 4 reaches the level of Toy Story 3 s crushing denouement. It feels as though we've already said goodbye to these characters, so saying goodbye again doesn't have quite the same impact as it may have otherwise. It's as if we just said a tearful goodbye to a relative and watched them drive off into the sunset, only to return to run back into the house real quick because they forgot their keys. It's nice to see them again, and we all had a good laugh, but the previous goodbye was much more emotionally satisfying.

Comments