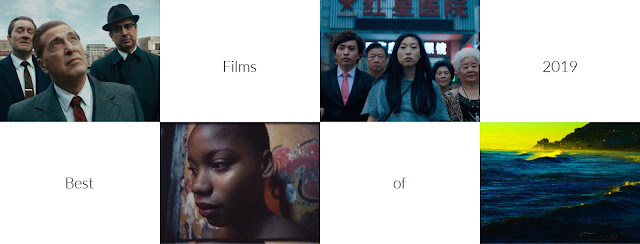

Year in Review | The Best Films of 2019

2019 was a year of great change. It was also a great year for film. Not only is the world facing unprecedented political upheaval and social change, both positive and negative, it was also the year I became a father, and welcomed my first daughter into the world. It's enough to make anyone look at the world a little differently. Did that affect my choices for the best films of the year? It might be too soon to tell. But for the first time in a long time - almost everything that was supposed to be good actually was. The 2010s saved the best for last and went out on a high note, delivering late period masterworks from old-guard legends like Martin Scorsese, Jean-Luc Godard, and Pedro Almodòvar to bracing new works by exciting new talents like Kalik Allah, Lulu Wang, and Hu Bo. It's a year that will go down in the history books for many reasons - but the films represented here will certainly ensure that this truly was a year to remember.

1. THE IRISHMAN (Martin Scorsese, USA)

It took Martin Scorsese nearly 10 years to develop and make his epic mob drama, The Irishman, a sprawling portrait of the rise and eventual decline of mafia hitman, Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), and his friendship with two equally charismatic and powerful figures - mob boss Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci) and infamous union leader Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino).Scorsese shoots the film's murders with a dry sense of matter-of-factness, characters casually stroll into frame, gun down an unsuspecting victim, then calmly walk out of frame again, leaving the lifeless body to bleed out on the sidewalk. There's nothing glamorous about it, but neither is particularly repulsive - it's just business, nothing personal, and that's what makes it all so disturbing. What kind of effect does a life like that have on a man? That's the question that lies at the film's sorrowful heart. Frank Sheeran spent a lifetime painting houses (a mob term for caring out hits; in other words, decorating walls with blood), while Scorsese has spent a great deal of his career chronicling the lives of men like Frank. In that regard, The Irishman feels like the summation of a career, a late-period masterpiece that takes into account a life's work. It is perhaps one of Scorsese's most reflective films, a broad-ranging meditation on life, mortality, and betrayal through the eyes of an old man in twilight, all his friends gone in violent ends, facing the end alone. Are we to feel sorry for him? To pity him? Or perhaps mourn the existence of the violent patriarchal power structures he spent a lifetime upholding? What are we to make of such a man? In Scorsese's masterful hands it becomes an American tragedy writ-large, of great potential cut down by greed and corruption, and a road to hell paved by the best of intentions. Scorsese, De Niro, Pesci, and Pacino, four lions in winter, all deliver some of the finest work of their respective careers in a film that can only be described as a monument of American cinema.

2. BLACK MOTHER (Khalik Allah, USA)

It's a rare thing to be left speechless by a film. Even more so for someone who writes about film for a living; yet Black Mother is the kind of film that defies description, a work of such radical beauty that it nearly reshapes the entire cinematic experience in its own image. Part documentary, part travelogue, part poem, Black Mother is a deeply personal tribute to Jamaica (the ancestral home of Allah's mother) and to the black experience, specifically the black women who actually birthed a nation.Allah examines the effects of religion on the tiny island nation, both as a symptom of colonialism and a reaction to it, as Christianity and Rastafarianism blend together into something beautiful and unique. Allah, a renowned photographer, captures snippets of island life and blends them together into something singularly breathtaking. There are films that move you, there are films that shake you, and then there's Black Mother - a transcendental meditation on life, love, and black identity that takes the mundane and makes it feel miraculous.

3. THE FAREWELL (Lulu Wang, USA)

While very specifically based on director Lulu Wang's affection for, and feelings of alienation from, her Chinese heritage, there's something very universal about the family dynamics on display in her deeply personal film, The Farewell.Awkwafina stars as Chinese expatriate Billi, who returns to China from the United States upon learning that her Nai Nai (Zhao Shuzhen) has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. But in a uniquely Chinese tradition, the family refuses to tell her that she's dying, instead disguising the impromptu family reunion as a wedding. Billi's struggle with the ethics of this deception form the core of the film; torn between her Chinese heritage and her American upbringing, she often feels like a stranger in her home country, a nation her family fled seeking greater opportunity when she was only a child.

And yet, while the film's central conflict is based on a very specific sense of cultural malaise, what Wang has crafted here is something immediately recognizable, a portrait of unconditional love that transcends the idiosyncrasies of familial bonds. Wang imbues her tale with such a sense of dignity and grace, writing a love letter to her beloved grandmother that just may make you want to run home and hug your own.

4. THE IMAGE BOOK (Jean-Luc Godard, France)

Jean-Luc Godard's The Image Book is at once perfectly at home with his other late-period collage films such as Film Socialisme and Goodbye to Language, and yet completely unlike anything the 88-year-old Nouvelle Vague iconoclast has ever made. It's part of the filmmaker's quest to investigate and reinvent the cinematic language, a life-long passion for Godard at least since 1967's WEEKEND, in which he infamously declared the "end of cinema."Through re-tooled images from cinema history (taken from such films as Luis Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou, Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar, Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, and Ridley Scott's Black Hawk Down) and an often shifting aspect ratio, Godard is quite literally making the audience look at these familiar images from alternate points of view. It's an effect created by the way Godard transfers films from VHS to his DV camcorder, as the camera attempts to adjust to the different aspect ratio, yet this digital "mistake" was purposefully left in.

The value of these images, in fact the very nature of their beauty (or lack thereof) lies in our own perception of them. Godard gives us the tools to decode them, but intentionally leaves us without a guidebook. Through the various lenses he places in front of them, be they digital imperfections, analog glitches, or simply the fog of time, The Image Book asks us to look at the world around us in ways we've never before considered. It's an endlessly fascinating and somehow wistful work, a career summation by a legendary iconoclast who continues to reinvent himself well into his ninth decade of life, now looking back at a life's work and asking "what was it all for?" The answer lies somewhere buried in the bleary fragments of images recorded from Godard's VHS player, a radical reinvention of cinematic language that will be studied and appreciated for decades to come.

5. AN ELEPHANT SITTING STILL (Hu Bo, China)

This is clearly a film that came from a very dark place, but that's what makes it so revelatory. Few other films have captured the essence of depression so indelibly. It's a work of incredible anger and anguish, but it's also a tremulous and delicate thing, epic in length but intimate in scope, a film that constantly turns its focus inward. Some may consider this insular, but Fan Chao's expressive camerawork turns the pain of the characters into outer expressions of sadness. It's as if the film was conjured from thin air, gorgeous, elemental, and tortured, Hu's consciousness made manifest and brought into being by sheer force of will. That final ray of light found in togetherness is what makes it all worth it - a note of hope that Hu never afforded himself. This light in the darkness in the form of an elephant trumpeting in the pitch black of the Mongolian desert is a moment so piercing that it almost seems like a cry from Hu himself - a warning, an admonition, or perhaps a word of comfort that it doesn't have to end the way it did for him. No matter how you interpret it, An Elephant Sitting Still stands as a monument to a tremendous unrealized talent taken from us too soon, who left behind an unforgettable meditation on what it means to cling to hope when the world around you seems utterly bleak.6. AD ASTRA (James Gray, USA)

In the most simplistic terms, Ad Astra feels like a Terrence Malick film with space pirates, a probing, philosophical film filled with lyrical musings about the nature of life, set against the epic backdrop of a world whose greed for natural resources has spilled over into outer space, as nations vie for supremacy not only on Earth, but on the moon as well. It is an adventure film but mainly in the sense that it’s about the mystery of exploration, but Gray’s aim is always much deeper than that.Gray paints on such a grand scale but the film never loses its intimate focus. That’s perhaps its greatest irony - Gray employs breathtaking cinematography and stunning special effects to tell a story that stands in stark contrast to its sweeping appointments. It is a deeply introspective film, the juxtaposition of its inner focus against a magnificent backdrop reinforced his central theme - even in the face of the loftiest of human achievement, nothing is more powerful or more important than human connection. What is the point of it all if we don't have love?

Its protagonist, like his father before him, is a man who put work above all, his singular drive to go higher, farther, and faster leading him to completely forsake his family. In the end it’s seemingly all for naught. What if we truly are alone in the universe? What if we spend our entire lives looking for something more, something greater than ourselves, and in the process miss, to paraphrase Dorothy Gale of Kansas, the beauty of what’s in our own back yard? Whether it’s over the rainbow or beyond the reaches of Neptune, Gray can’t help but remind us that nothing is so grand and mysterious and worth our time as love. Ad Astra is one of the best works of science fiction this century.

7. PAIN AND GLORY (Pedro Almodòvar, Spain)

Cinema history is littered with filmmakers who turned the camera on themselves - stories of tortured artists, great men burdened great talent. It would be easy to dismiss these films as mere vanity projects, tales of self-aggrandizement by mostly male filmmakers who see themselves as saddled with great genius that no one else could possibly understand. However, there's something much more humble and self-reflective in Pedro Almodóvar's Pain and Glory, an ostensible act of self-reflection that seems to flow directly from the filmmaker's heart rather than his own ego.It is through his protagonist, an obvious avatar for Almodóvar himself, that the filmmaker subverts the trope of the struggling genius and the women who inspired him, putting a queer twist on what has become a kind of cinematic indulgence for straight filmmakers. Here we see a gay filmmaker baring his soul and exploring the roots of his own sexuality in ways once only afforded to straight artists, and the results are bracing and often deeply moving. This is not the same Almodóvar who made Matador and Law of Desifre - this is a film that finds the filmmaker in a much more reflective mode, more reminiscent of his work in Bad Education, a film with which Pain and Glory shares a similar thematic outlook. Yet by the time the film reaches its wrenching, revelatory conclusion, Almodóvar manages to re-contextualize everything we've just seen. It's one of the most stunning film endings of the year, and yet it's so quietly earth-shattering that its power is almost disarming. It's the kind of film that cements Almodóvar in the pantheon of great artists, and it does so without ego or pretense, an understated glory that finds devastating beauty in the wreckage of a lifetime of mistakes and missed opportunities as only the cinema could have given us.

8. LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT (Bi Gan, China)

Much has been made about the one-shot prowess of Sam Mendes's 1917, and while that film is certainly a dazzling achievement, the year's most impressive single take shot is in Bi Gan's neon-soaked Neo-noir, Long Day's Journey into Night.Like something out of a dream, Bi takes us on a journey through time and memory, plunging us into its protagonist's tortured search for a mysterious woman from his past. Before long we find ourselves deep into a mystery for which there may be no answer, at once an existential nightmare and an Antonioni-esque exploration of the human mind. Its final, hour-long single take tracking shot is not only a marvel of technical ingenuity, it's like an out-of-body experience that shatters the boundaries of what cinema can do.

9. A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD (Marielle Heller, USA)

Marielle Heller's A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is a much darker, more complicated film than its marketing would suggest. While Tom Hanks' Mr. Rogers has been at the forefront of the film's marketing campaign, the film really isn't about Mr. Rogers at all; it's an emotionally thorny family drama about a cynical and wounded man coming to terms with his trauma and taking the first steps toward mending the rifts in his family.This movie goes to some dark places, but it emerges hopeful. No other film this year has felt quite so cathartic. It’s not so much about Mr. Rogers as it is the idea we all have of him - and rather than deify him, it humanizes him, as a human being like all of us, but who found a way to deal with the hurt inside. There's some really emotionally complex, powerful stuff here, and Heller navigates it with great care, deftly speaking to the part of all of us where child that we were meets the adult that we are.

That final shot of Mr. Rogers alone in his studio banging on his piano are going to stick with me for a long time. They’re beautiful notes, but those few dissonant chords suggest a more complex emotional life than perhaps we saw. And yet nothing about him feels fake or inauthentic. Mr. Rogers was the man we saw on TV. He remains a symbol for all that is kind and good; but the film, like the man, invites us to grapple with and acknowledge the negative feelings inside. People hurt. They feel sadness, anger, regret. But to embrace those things, to meet them head on and wrestle with them rather than sweeping them under the rug - that’s a good feeling.

10. HOTEL BY THE RIVER (Hong Sang-soo, South Korea)

Filled with longing and regret, Hotel by the River is the story of a group of quintessential Hong protagonists, separated by emotional distance they are unable to bridge despite their best efforts. It recalls the snowy wistfulness of The Day He Arrives (2012), centering around five lonely people who converge on the eponymous hotel to find their own definition of peace and healing.

On the surface, Hong's films often seem aimless and meandering. And while Hotel by the River is perhaps his most accessible film in recent memory (and the first of two films released in 2019, including the enigmatic Grass), it still retains his trademark unassuming self-reflexivity, the characters seemingly trapped in a self-imposed purgatory for which they hold the keys to escape, yet never quite figure out how to use them. One always feels that Hong's films are an attempt by the filmmaker to exorcise his own demons, to explore his own feelings and shortcomings both as an artist and a human being. There is a poignant sense of regret that permeates the film that is both tangible and intoxicating, and one comes away with the feeling that we're all just snowflakes in a snowstorm, colliding with each other briefly as we're tossed in the wind, searching for somewhere to land. In Hong's haunted meditation, there is no pretense of having all the answers, and that's what makes it so special. He's out here trying to figure himself out just like everyone else. Like his very best films, Hotel by the River seems like a circuitous trifle on the surface, but within its modestly composed black and white frames lies a profoundly open-ended exploration of the very faults, foibles, dreams, and contradictions that makes us human.

11. ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD (Quentin Tarantino, USA)

Going into a Quentin Tarantino movie, one usually has a certain set of expectations: there will be copious amounts of violence, creative (and constant) use of curse words, extensive references to older films, and lately, a new spin on familiar history.

His latest film, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, checks all those boxes, but for the first time since perhaps 1997's Jackie Brown, there's something much deeper and more melancholy at work here. Tracing the story of a former TV western star named Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his faithful stuntman, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), Once Upon a Time in Hollywood transports us back to the summer of 1969 in the city of dreams, where anything was a possible but change was inevitable.

It's almost as if Tarantino is grappling with his own anxiety about pending irrelevance and ennui while honoring the great filmmakers of the past whose work has been so important to forming his own career. Tarantino famously proclaimed that he would retire after making 10 films, and for those keeping score at home, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is his ninth (if you count the two volumes of Kill Bill as one film). The result is perhaps the most beautiful, wistful, and touching thing he has ever directed. The unexpected gravitas and lugubrious self-reflection is something quite new for the filmmaker, displaying a sense of mournful contemplation in a sanguine tribute to the heroes of his childhood. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is easily Tarantino's most deeply felt film to date. Beneath his instantly recognizable sense of dark humor, it's a pensive and haunted reverie of the fading shadows of old Hollywood, where dreams unfolded in larger than life images on a flickering screen, created by much smaller men and women who were more fragile and flawed than they ever let on.

12. THE LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO (Joe Talbot, USA)

There's an unshakable sense of sadness at the heart of Joe Talbot's freshman feature film, The Last Black Man in San Francisco. It centers around a young man named Jimmie who obsessively returns to the home his grandfather built upon moving to San Francisco after WWII, much to the chagrin of the current owners, who don't appreciate Jimmie's constant repairs and improvements. Jimmie's father lost the house due to financial mismanagement, but that hasn't stopped Jimmie from trying to take care of it when the new owners let it fall into disrepair. When the house finally comes up for sale, Jimmie is determined to reclaim his birthright and buy his childhood home, but the multimillion dollar price tag may prove prohibitive in the newly trendy neighborhood.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco touches on ideas of gentrification as Jimmie's former neighborhood suddenly becomes a hot commodity among affluent young white people, but Talbot digs deeper than that, exploring themes of home and identity, and how those two things are often inexorably linked. But in tying his identity to a location, Jimmie discovers some hard truths about where he's really from, and is forced to grapple with what that means for his future. Both Jimmie Fails (who co-wrote the screenplay based on his own life) and co-star Jonathan Majors are remarkable, but it's Fails' sensitive screenplay that is the star here. It's a work of quiet, unassuming beauty. A probing, deeply personal exploration of his own family history and his love for the place he calls home - San Francisco. It's at once a love letter and a warning. "You don't get to hate it unless you love it," he admonishes a young carpetbagger complaining about her newfound surroundings. And indeed, Fails' criticisms are nothing if not full of love for the city of his birth.

Talbot takes the mundane and makes it ecstatic, soaring on the wings of Emile Mosseri's haunting score, a mix of mournful oboes and wistful pianos that feels at once familiar and alien, like returning to a home you no longer recognize. It's a beautiful achievement, and one of the very best films of 2019.

13. CHINESE PORTRAIT (Wang Xiaoshuai, China)

Most films are primarily concerned with action and movement - how characters get from "Point A" to "Point B." Figures moving through space and time, in and out of frame, conducting the business of moving along the plot.

By contrast, Wang Xiaoshuai's documentary, Chinese Portrait, is a movie about waiting, focusing on the seemingly mundane moments between actions that most movies cut around. The film consists of a series of static tableaus set in textile mills, homes, mines, trains, and other everyday locations of Chinese life. By posing the subjects in a kind of cinematic still life, Wang creates a kind of non-reality reality, a snapshot in time that could almost be a still photograph if it weren't for the life continuing on around them. It almost feels like the mirror image of Abbas Kiarostami's 24 Frames, but instead of animating still images, it's freezing real life moments like an insect preserved in amber, a piece of seemingly arbitrary time captured and preserved forever.

One might expect a film comprised of mostly static tableaus to become tiresome or dull, but as the film progresses it becomes something at once wondrous and revelatory, a dynamic living document of modern China that invites viewers to take in the world around them, to become enveloped by its fluctuating scenarios. The effect is at once riveting and enchanting, a quietly electrifying avant-garde documentary that creates a clear-eyed portrait of our ever-changing world without ever uttering a word.

14. PARASITE (Bong Joon-ho, South Korea)

Parasite begins as a seemingly light-hearted family comedy, Ki-taek's brood spending their time desperately searching for the one spot in the house with a wi-fi signal, and chasing off drunks who constantly piss in front of their window. Even their ingratiation with the Park family plays a bit like a farce. But Bong slowly turns the film into something else, a dark thriller built around an outlandish premise that finally comes to a head in a shocking eruption of violence, before switching gears yet again into a kind of reflective socially conscious tragedy. It's a film very much rooted in class consciousness and income inequality, an issue that continues to rise to the forefront not only of our own politics here in the United States, but in countries around the world. Bong masterfully blends these divergent genre elements into one wildly original whole, crafting an incisive indictment of income inequality and the wide gulf between the classes that is as bitterly funny as it is hauntingly wistful. It's a tale of two families living side by side who couldn't be further apart, with one family propping up and enabling obscene wealth they could never hope to accumulate in a thousand lifetimes. That's the real tragedy at the heart of Parasite it may be about tensions between the haves and the have-nots, but it's a stark reminder that the have-nots need the haves just as much as the haves need the have-nots, and that such extreme inequality can only ever lead to simmering resentment that will inevitably boil over.

15. CLIMAX (Gaspar Nöe, France)

Climax is the perfect movie for the world in which we live. Common morality and human decency take a backseat to something much more brutal and primal, a world run by pure id. Yet this is no empty provocation, it’s an exploration of the darkest recesses of the human mind, a window into what we're capable of at our very cores. There's a kind of trance-like quality to the film, and once we're under Noé's spell, there's no turning back. It's at once a slow-burn unravelling and a turbulent, unhinged party that goes quickly off the rails. That Noé manages to balance those two aesthetics is remarkable in and of itself, but to also create something that is as moving as it is horrifying. Climax is often shockingly brutal, but it manages to make us feel the pain of its characters, and to sympathize with their plight. They never asked for this, and the results are often terrifying.

Much of the film is shot in long, unblinking takes, the camera movements replacing editing by being untethered to one specific plane. Noé's camera moves throughout the party like an unseen observer, roving the halls, and even moving up to the ceiling for a bird's eye view so that the audience is at once a dispassionate voyeur and an active participant. There's simply no other film like it in recent memory. It's thrilling, ghastly, tragic, and beautiful, a riotous and sensual visual and aural assault that simply must be seen to be believed.

Comments