Blu-ray Review | "The Cinema of Jean Rollin Pt. 3"

One of the absolute cinematic pleasures I have had over the last year has been discovering the films of French horror auteur, Jean Rollin, thanks to Kino Lorber's excellent blu-ray treatments (10 of which have been released throughout 2012).

It's tempting to brand Rollin as a schlock-meister. But he's so much more than that. His often bizarre and surrealistic films, filled with producer imposed erotica and gratuitous nudity may appear, on the surface, to be little more than trashy European exploitation films. Yet when one digs a little deeper you find recurring themes, surprising intelligence of construction, and original form. Rollin toys with our expectations, subverting convention at every turn. Whether or not those experiments are successful or not is up for debate.

Sure there have been some duds among them, chiefly his first film, the utterly nonsensical The Rape of the Vampire (1968). But more often than not, even when they are buried beneath seemingly needless sex scenes and hampered by his lack of budgets, Rollin's films exude a kind of life and energy that is hard to ignore.

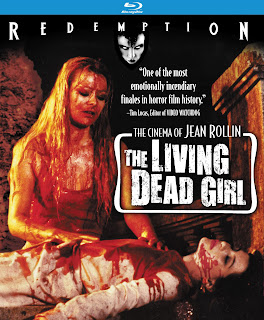

The first film in Kino's third wave of Rollin titles is his 1982 oddity, The Living Dead Girl. More violent and with a greater focus on gory makeup effects than his previous films, The Living Dead Girl offers a truncated and compromised version of Rollin's vision, but its also one of his most straightfoward and accessible works. Made at a time when the slasher genre was at the height of its popularity (John Carpenter's Halloween had started the craze just five years prior, and the Friday the 13th franchise had already churned out three entries in the series by '82), the film was made to capitalize on a world where extreme violence was the new norm. What sets Rollin's films apart is that his "objectified" females are not the victims - they are the monsters. Yet he asks us to identify with them, to care for them. They are at once the bringers of death, and the picture of innocence; that dichotomy standing in stark contrast with the usual cliches of the genre.

The film centers around a young girl who is resurrected from the dead by a toxic spill, and is taken care of by a childhood friend in an old abandoned castle. The girl, Hélène (Marina Pierro), neither alive nor dead, must feed off the flesh of the living in order to endure, and her best friend, Catherine (Françoise Blanchard), must lure unsuspecting victims to the castle for Hélène to devour. While not twins, as is a recurring theme in Rollin's work (see Lips of Blood), the relationship between Hélène and Catherine provides the backbone for the film, something we see often throughout Rollin's filmography (Requiem for a Vampire, The Demoniacs, Two Orphan Vampires). In The Living Dead Girl, unlike in, say, a film like Friday the 13th, the killer is not just a symbol of faceless evil. Whereas Hélène remains symbolically innocent, almost pure, it is her friend Catherine, and her entrapment of unsuspecting victims, who is the true monster. Hélène cannot help the way she is, and is therefore relieved of any culpability in her own actions. She did not ask to be brought back to life. Catherine, on the other hand, absolutely knows what she is doing, yet does none of the killing herself. Rollin invites us to consider which is worse.

Two Orphan Vampires is, in some ways, an extension of the themes of The Living Dead Girl. Whereas Living Dead Girl is a more straightforward gore film (and is therefore more well known among horror fans), Two Orphan Vampires marked something of a return to Rollin's surrealistic form. It's strange, however, that a film released in 1997 is more dated than his work from the 1970s and 80s, but it feels like something of a relic. Even its transfer is subpar, surprising considering that the blu-ray of The Living Dead Girl is perhaps Kino's best work of the Redemption titles.

As one of Rollin's late period films, Two Orphan Vampires marked not only a return to form for the auteur, but a return to the vampire genre, which he had not worked in for over two decades since the release of Lips of Blood in 1974.

Rollin was in failing health when he made this "come back" film, often directing some scenes while laying down, and passing off the New York shoots to a second unit director. And indeed the film itself seems tired, more like an afterthought to an illustrious career.

Inspired by the classic French novel, "Les Deux Orphelines" by Adolphe Philippe d'Ennery and Eugène Cormon (which also served as the basis for D.W. Griffith's Orphans of the Storm in 1921), Two Orphan Vampires follows two orphan girls who pretend to be blind during the day, but at night steal away from the orphanage to prey on the blood of the living. It's a relatively unremarkable film, both in terms of the genre and in Rollin's personal canon. In fact it is the weakest of the 10 Rollin titles that Kino has released by far. While there is a certain dreamlike quality to it that recalls Rollin's earlier work, it seems faded and lacking in that certain joie de vivre that seemed to mark his earlier work. Rollin, it seems, had lost his touch.

However, in the film's final moments, Two Orphan Vampires suddenly becomes something remarkable. It is not enough to make up for the rather dull 90 minutes that preceded it (which is filled with bizarre references linking vampirism to Aztec mythology), but Rollin subtly subverts everything we have just seen with the suggestion that everything up until the end was just part of an elaborate fantasy constructed by two lost and troubled little girls, who built their own world where they have all the power as a way of dealing with the misery of reality. Or perhaps it wasn't. Who knows? It is an unexpected emotional sucker punch in a film that heretofore had shown no glimmer of humanity. It is, perhaps, one of the most mature and beautiful moments in the Rollin canon (rivaling the blistering coda of The Living Dead Girl), made even more poignant by the fact that this was one of the last films Rollin would ever make before his death in 2010. In fact it seems to sum up the full thematic spectrum of his filmography in one, wrenching moment, when fantasy and reality finally collide in a moment of haunting nostalgia for a reality that perhaps never existed.

That makes Two Orphan Vampires a fitting companion for The Living Dead Girl. Whereas The Living Dead Girl is perhaps the most un-Rollin like of his horror films (not counting 1981's Zombie Lake, which has yet to be released by Kino), it still finds a way of subverting our expectations even in the face of crippling studio demands. Two Orphan Vampires, on the other hand, is a much more pure Rollin experiment. One that perhaps does not work as well as some of his earlier triumphs such as The Iron Rose or Fascination, but even his failures contained something special. Rollin was a unique talent, an artist working at the behest of smut peddlers (not unlike Val Lewton, who often elevated low budget schlock like I Walked with a Zombie and Cat People into a higher form of art) whose work, at long last, is finally being appreciated thanks to the miracle of home video, and can now be seen in their most stunning quality ever thanks to the folks at Kino Lorber.

THE LIVING DEAD GIRL - ★★★ (out of four)

TWO ORPHAN VAMPIRES - ★★

Now available on blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber.

It's tempting to brand Rollin as a schlock-meister. But he's so much more than that. His often bizarre and surrealistic films, filled with producer imposed erotica and gratuitous nudity may appear, on the surface, to be little more than trashy European exploitation films. Yet when one digs a little deeper you find recurring themes, surprising intelligence of construction, and original form. Rollin toys with our expectations, subverting convention at every turn. Whether or not those experiments are successful or not is up for debate.

Sure there have been some duds among them, chiefly his first film, the utterly nonsensical The Rape of the Vampire (1968). But more often than not, even when they are buried beneath seemingly needless sex scenes and hampered by his lack of budgets, Rollin's films exude a kind of life and energy that is hard to ignore.

|

| A scene from THE LIVING DEAD GIRL. Image courtesy of Collections La Cinémathèque de Toulouse. |

The film centers around a young girl who is resurrected from the dead by a toxic spill, and is taken care of by a childhood friend in an old abandoned castle. The girl, Hélène (Marina Pierro), neither alive nor dead, must feed off the flesh of the living in order to endure, and her best friend, Catherine (Françoise Blanchard), must lure unsuspecting victims to the castle for Hélène to devour. While not twins, as is a recurring theme in Rollin's work (see Lips of Blood), the relationship between Hélène and Catherine provides the backbone for the film, something we see often throughout Rollin's filmography (Requiem for a Vampire, The Demoniacs, Two Orphan Vampires). In The Living Dead Girl, unlike in, say, a film like Friday the 13th, the killer is not just a symbol of faceless evil. Whereas Hélène remains symbolically innocent, almost pure, it is her friend Catherine, and her entrapment of unsuspecting victims, who is the true monster. Hélène cannot help the way she is, and is therefore relieved of any culpability in her own actions. She did not ask to be brought back to life. Catherine, on the other hand, absolutely knows what she is doing, yet does none of the killing herself. Rollin invites us to consider which is worse.

Two Orphan Vampires is, in some ways, an extension of the themes of The Living Dead Girl. Whereas Living Dead Girl is a more straightforward gore film (and is therefore more well known among horror fans), Two Orphan Vampires marked something of a return to Rollin's surrealistic form. It's strange, however, that a film released in 1997 is more dated than his work from the 1970s and 80s, but it feels like something of a relic. Even its transfer is subpar, surprising considering that the blu-ray of The Living Dead Girl is perhaps Kino's best work of the Redemption titles.

As one of Rollin's late period films, Two Orphan Vampires marked not only a return to form for the auteur, but a return to the vampire genre, which he had not worked in for over two decades since the release of Lips of Blood in 1974.

Rollin was in failing health when he made this "come back" film, often directing some scenes while laying down, and passing off the New York shoots to a second unit director. And indeed the film itself seems tired, more like an afterthought to an illustrious career.

|

| A scene from TWO ORPHAN VAMPIRES. Image courtesy of Collections La Cinémathèque de Toulouse. |

That makes Two Orphan Vampires a fitting companion for The Living Dead Girl. Whereas The Living Dead Girl is perhaps the most un-Rollin like of his horror films (not counting 1981's Zombie Lake, which has yet to be released by Kino), it still finds a way of subverting our expectations even in the face of crippling studio demands. Two Orphan Vampires, on the other hand, is a much more pure Rollin experiment. One that perhaps does not work as well as some of his earlier triumphs such as The Iron Rose or Fascination, but even his failures contained something special. Rollin was a unique talent, an artist working at the behest of smut peddlers (not unlike Val Lewton, who often elevated low budget schlock like I Walked with a Zombie and Cat People into a higher form of art) whose work, at long last, is finally being appreciated thanks to the miracle of home video, and can now be seen in their most stunning quality ever thanks to the folks at Kino Lorber.

THE LIVING DEAD GIRL - ★★★ (out of four)

TWO ORPHAN VAMPIRES - ★★

Now available on blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber.

Comments